Juvenile Delinquency and Failed Adolescence in Scum (1979) and Bad Boys (1983)

And the drastically different approaches taken in both movies.

Bad Boys is a movie about teenagers getting into some really awful situations – directly about a scenario of people who are casted as hopeless youths, about a 16-year-old named Mick O’Brien who winds up in prison with a rap-sheet a mile long – after winding up killing an eight-year-old boy during a robbery gone wrong, then finding out the hard way that prison life is an absolute hell-hole.

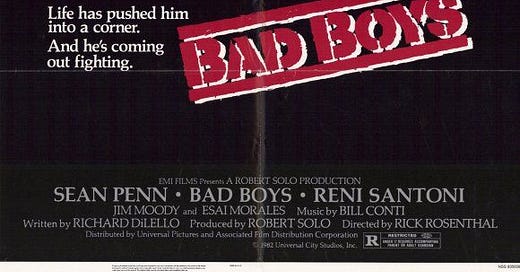

Sean Penn was probably best known for his role as Jeff Spicoli in Fast Time at Ridgemont High (1982) when this movie came out. This poster also had quite a memorable tagline as well.

This movie commonly got a reputation as something which absolutely terrified teenagers who watched it – dissuading people from ever wanting to go to prison, and it is depicted in this incredibly harsh and confrontational light. Nothing about how the prison works here is seen as even remotely enjoyable or functional – and it very much depicts it as a hell-hole where only violence and gang activities proliferate there, almost an extension of the life on the streets. Most everyone inside is aware of just how terrible the prison system is, but then Mick initially treats the prospect of prison as though it were essentially along the lines of a paid vacation. But then what we also see of Mick’s life revolves around a routine of high school bullies – and of gang wars bubbling underneath the surface, and of negligent, alcoholic parents who only acknowledge their son’s existence when it begins to annoy them.

But then where this movie also works comes from the confrontation of the value systems of the street youths and the people running the prison – notably with how it highlights how adults and kids alike can come to these weirdly contradictory viewpoints in terms of status and what has to be done. It never really glamorises street-crime – especially with how the shootouts and all the violence as casted as intentionally disturbing without much room for catharsis, and the status gained in it is pretty much only compulsive. And the first few segments of this film are basically just an escalating string of crimes performed by Mick – easily where he’s able to obtain a gun from a young teenaged kid and culminates in him becoming involved with a street robbery which goes wrong.

Mick is accused by a judge of presenting deeply sociopathic behaviour – but then there’s a lot in his life where it’s very much a case of severe alienation, he only seems to get into fights at school, he lives with his parents who are neglectful as all hell – and he views his gang activities as something which gives him at least somewhat of a margin of status in the world. Even the guard Ramon admits “I was into that gang shit for half my life. It’s dumb, fucking nowhere shit.”, and there’s also the interesting thing with how certain prisoners got here. There’s a great character in this film called Horowitz who is this small wise-ass kid who partners up with Mick, and he becomes something of a strange comedic foil where he perceives himself as someone who likes to play pranks on people - then we soon find out about the genuinely grisly shit he performs under the guise of a 'prank’ and just what he perceives as a joke.

However, there’s also a scene where Mick escapes prison before eventually being tracked down by Ramon – where he sees Mick consoling his girlfriend after she had just suffered a brutal assault. The scene is really bittersweet and poignant, and also has Ramon coming across as strangely compassionate towards O’Brien – genuinely understanding with why he performed the escape attempt, then it’s followed by this scene.

Of what is supposedly a ‘real-time’ prison.

Which is such a tonal whiplash but the scene itself is very much deliberate, and later his situation is somewhat excused under ‘extraordinary circumstances’ – but there’s just so much going on with that one scene along. Quite a lot of this movie is effective pretty much on that level alone, where it’s just these simple but incredibly powerful statements – and just that transition alone sums up the tone of this movie fairly well.

Although there’s a fair share of it which is a bit too dependent on sentimental moments and this weird, almost forced structure where it’s all escalating towards this final showdown between Mick and Paco – but then there’s a strange sort of inevitability towards it, and how it goes against our expectations of seeing Mick come out as this reformed prisoner. And just about how it’s clear that all the odds are stacked against him – and just about all of this collateral damage which keeps building and building. There’s a great line from the prison guard Ramon which is as follows:

“Outside everyone gets on with their lives. Working, making money, getting laid, all that good shit. But in here, time just stops dead.”

But then also what opportunities are there for these kids? On one hand it very clearly depicts the prison system as being this nightmare scenario – which proves to be invariably cyclic as the film goes on, that it’s something that should be avoided. But then it’s also not solely a scare movie about something as simple as “Don’t do dumb shit and you won’t go to prison.” – but also being incredibly confrontational of the underlying culture, and of the underlying systemic issues that lead onto incidents like this. It works both as a sobering reminder not to get into situations like this – but also calling a direct attention to the fact that maybe we’re failing these kids, and maybe we should do something to fix it.

Source: http://static.cinemagia.ro/img/db/movie/15/98/23/scum-209825l.jpg

However, the movie Scum (1979) is much more pointed – instead where it sees the systemic failings much less as something which can be fixed, and moreover sees it as a system where it’s functioning as intended. The disparities are the point and the prison system itself could only operate with those disparities in place – something that the movie is willing to remind you off right from the get-go, with a scene where Carlin is introduced and he’s explicitly told “There is no violence here.” before being suggestively looked at by one of the guards and punched in the stomach repeatedly.

This movie is hardly subtle, but Clarke himself was also both incredible with British social realist dramas but was also an incredible satirist – something that is explored a bit more explicitly in movies such as The Firm (1989), which was an indictment on the modernisation of football hooligan culture – especially showcasing the disparities in class and with the obsession towards football culture and what winds up being neglected in the process. And way more explicitly with the movie Rita Sue and Bob Too (1987) which is an incredibly bawdy sex-comedy, but then also where it’s very much interested in placing you in despairing scenarios and highlighting themes of poverty and boredom in a working-class neighbourhood – especially with the clearly unfair power dynamics between Bob and Rita and Sue, and it’s very much a common theme running throughout his works.

Scum itself is not quite a satirical movie, but then it’s also something that does have its share of moments where it can be weirdly funny but also deeply horrifying with the implications behind it. A pivotal scene in this film revolves around the character Archer sits down to have a conversation with one of the guards Duke – where clearly the guard is fed up and sees his job as incredibly exhausting but somehow weirdly necessary. The conversation itself starts off fine and Archer makes a few valid points about the prison system, something that Duke is initially receptive of – then it reaches a point where it becomes a bit too confrontational for his liking, instantly Duke flips and he mechanically calls out “NAME AND NUMBER” before indicting him for insubordination.

This is a pretty long scene, but honestly it’s genuinely more disturbing through dialogue than most of the violence depicted in this film.

That’s pretty much the entire point of the movie right there – notably where it’s about how these institutions remain intact in the first place, despite the obvious and often deliberate failings of them. It’s presented so clear as day and it’s something that you can help but notice, but then more fundamentally the movie is also concerned about where these things come from and why they occur. The guards themselves are deliberately in a position where they never confront their humanity – instead where they are just completely mechanical, and they only really seem to emote themselves through anger, scorn, and just where everything is swept under the rug. Even then there’s also something where they seem to understand the seriousness of the situation in terms of raw emotions, but then it’s also clearly manipulative – especially with how their reactions are the exact opposite of what any decent person would do given the situation.

But then there’s also an interesting paradox with how they understand the harshness of prison, and at points they seem to act compassionate towards certain prisoners – except it’s clearly preferential treatment which only comes in specific situations where they can exploit the person or they can frame themselves as having done something good, otherwise it comes across as cold and uncaring – even in literal life-or-death situations. This is also something that Carlin takes full advantage of – where he’s pretty much all but aware of how to gain full advantage in the system and is seen preferentially by the guards. Likewise, there’s the prisoner Archer who does everything he can in order to piss off the guards – in ways which are sneaky, but also heavily exploit and work around the system in place. Archer feigns being a vegetarian solely to get himself special requirements solely to piss of the guards, and in one scene Carlin hands him a sausage which he scoffs down in secret.

There’s a ‘joke’ wedding between a black guy and a white guy that takes place where the guards act like they’re doing something decent for the prisons – except that it explodes into violence which is ignited when the white prison says “I’m not marrying a fucking c**n.”, but the white prisoner is seen as more favourable whilst the black prisoner is scolded for it. Racism is also a heavy characteristic of the prison system – one in which the guards also heavily exploit it, and there’s so much done to highlight how the guards can act so incredibly hostile at one moment – then acting like it’s nothing the next, furthermore where it’s used to showcase the unwritten rules and all of the open secrets with how the prison is run.

And the whole film is composed like that where it’s all of these little incidents, ones in which there are all of these disparities which manifest themselves – and how everything here isn’t the natural order of things, but people treat it as such even when so much of it is clearly deliberate. Most of what’s actually reported on are incidents which are incredibly petty, and pretty much all of them fall in line with the mentality that “You’re not doing this properly. You’re not wearing your uniform/the appropriate gear. You’re not doing what the screws have specifically told you to do.” and so on - where it’s all done very excessively, and the harsh incidents are covered up by this attitude that mindless, tedious work will set these boys straight - only that it directly results in an environment which is a breeding ground for cruel behaviour.

This gets Archer (the person on the right) indicted by a very exacerbated guard - even if it’s clearly something that will go away when the job is finished.

Quite a lot of this movie has a tone where it’s simultaneously both funny but then it’s also grim as all hell - where it very much tends towards the latter towards the end of the film, especially with how the prisoners become increasingly more exacerbated with the BS they put up with. And furthermore it all feels like it’s just hurtling towards this final explosion – and the ending here is about as powerful as it is crushingly ironic, but furthermore illustrates the ultimate powerlessness of this situation – both where it’s incredibly frustrating, but it didn’t just come from nowhere – and in its own way it feels strangely inevitable but also entirely preventable.

Both of these movies are strangely similar - in fact, Bad Boys (1983) borrows a lot of elements from Scum (1979) - including the prison setting and the whole idea of prisoners who get special privileges (either a Daddy or a Barn Boss), although they are radically different in their approaches. Bad Boys comes from the tradition of American gang films during the late 1970s/early 1980s which include the likes of The Warriors (1979), Boulevard Nights (1979) and Rumble Fish (1983) - which felt more concerned with the temptations of gang life, although the disparities that led onto the situations were very much a thing illustrated in those films.

Whilst Scum is very much a British social realist drama - in the vein of people like Ken Loach or Tony Richardson, although Clarke’s style definitely has more of a satirical bent and much more of a confrontational rather than a didactic edge to it - in how much emphasis is placed on these tight and claustrophobic scenarios. I also happen to like Scum a lot more than Bad Boys - where it’s certainly a much rougher watch than Bad Boys, but it’s also way more confrontational with what it shows - where its criticisms of the system does not lie with how it just happens to fail young people, but just that its deliberately designed to fail young people - or at least those who prove that they can’t fall in line with what the people in charge want you to do.